A Famous Black Man Mentors a Young Southern White Man in . . . the 1930's Jim Crow South?

No, it's not Ripley's Believe it or Not... it's the unifying history we rarely see.

Yes, it’s a sarcastic title. I’m not going to apologize. When I was 17 and moved to Colorado, everyone thought the South was “Deliverance.” What (manufactured) ignorance!

Here’s the reality: Wonderful things happen all around us every single day; it’s been that way forever. The story this book holds is one of those wonderful occurrences.

*************

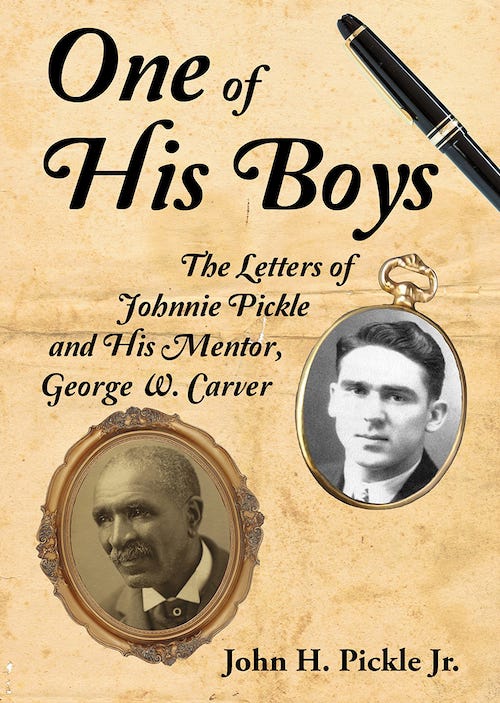

I picked up One of His Boys: The Letters of Johnnie Pickle and His Mentor, George W. Carver in May of this year, during a trip to southwest Missouri to visit the George Washington Carver National Monument.

I’d been corresponding with Park Ranger/Archivist Curtis Gregory for about a year (connected to my publication of Rackham Holt’s biography of George Washington Carver and was excited to finally visit this incredibly important historic place—the first national monument to honor a Black American AND a non-president.

Gregory and I shared a pleasant almost two-hour visit on all-things-Carver. It ended with me asking for book suggestions. Gregory reached for a small paperback book on a nearby bookshelf. “This is a new one about his mentorship of a young man from Mississippi during the ‘30s. It was written by his son. It’s good.”

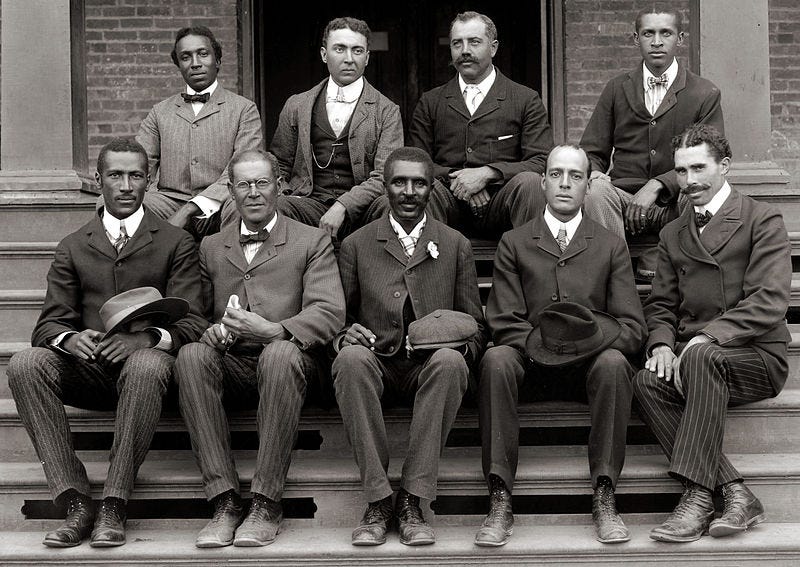

I said, “I can’t wait to read it!” I’d heard about “Carver’s Boys,” the young men he’d mentored during the last two decades of his life. Many were Black, but some were white; this book was about his relationship with a white college student. I was curious because there didn’t seem to be a lot of detailed information on those relationships.

When I got home, I read One of His Boys in one sitting. The book is based on letters between the famous scientist (born into slavery at the end of the Civil War) and Johnnie (John H.) Pickle, a white college graduate that Carver met in 1932 and mentored until 1938. It was put together by Pickle’s oldest son, John Jr., and published in 2021.

The author, John H. Pickle Jr., Ph.D., grew up knowing about the relationship between Carver and his father. In his teens (in the 1950s), he even happened upon the letters, some of which had mice damage, from Carver in an old dresser. He says he took the letters then, knowing they were important, and put them in a safer place. He says Carver had an enormous impact on their family’s values for multiple generations. Carver reinforced the values of living with integrity, placing a high value on education, engaging in meaningful humanitarian work, and connecting with the community. These values, among others, have been passed down to each generation of the Pickle family.

Johnnie Pickle and Carver met when Carver came to “Ole Miss” (the University of Mississippi) to lecture in 1932. Before his lectures, Carver often explored the wild areas looking for botanical and geological specimens to illustrate his talks. On this visit, student/nature-lover Pickle, then a senior and a geology major, was assigned to assist him. Their walk was conversation-filled and included many Biblical quotes from Carver that illustrated the things they were seeing in nature. The two men bonded deeply. Pickle later recalled, “The walk with Dr. Carver was like a day spent with God, where nature came to life and every single item took on a new meaning.” That time spent together was so impactful that Pickle, then 24, told Carver, then 68, that he wanted to visit Tuskegee after graduation.

That summer, Pickle hitchhiked to see Carver at Tuskegee University (then Institute) in Alabama, despite knowing that for “a white person to visit a Negro, if not unheard of, […] certainly wasn’t mentioned.” In spite of Jim Crow, he and Carver’s friendship deepened during this visit. Before Pickle left, Carver invited him to be one of “his Boys.”

Carver’s invitations for a mentorship relationship were only extended to young men who, Pickle Jr. writes, “had a Christian upbringing, were idealistic, had a college education and were looking to make their place in society.” Carver had to see something in these young men that went far beyond the ordinary, a passion to be an exceptional human being and a desire to live a life of service.

Young Pickle, who considered Carver “a gentleman and a Great Man in every sense of the word” was more than excited to accept this invitation.

The letters in this book reveal soul-baring thoughts about life, career, religion, and relationships, and Carver mentors Pickle through some difficult times both physically and emotionally. Pickle’s letters to Carver read like a son sharing life’s challenges, hopes, and dreams. The language reveals deep respect and the desire for not only guidance but approval. Carver’s replies read like a wise, loving, and doting father who applauds success and gives constant encouragement. Instead of directing his mentee to what he might personally think is the “right” path, he asks questions that will prompt Pickle to access his own inner wisdom.

The fun part for me was that Pickle’s letters often read like a hero’s journey. Imagine a handsome and promising but penniless young man who has just made it through college during the early Depression years. He’s the youngest of seven children and the only living son, as both his older brothers have died prematurely. His father has lost his business, a general store, due to the bank failures. Pickle decides to set out and continue his education—both for the practical hope that the job market will return in a few years but also because he’s committed to striving for a life where he can be of the most service to others. Jobs are scarce and low-paying, so he does what he can to keep body and soul together during his often-difficult quest. Pickle, who has the trust, drive, and the wide-eyed innocence of a young 20-something, is a person readers of all ages can identify with.

When Pickle begins his journey from Tuskegee, Alabama, to the University of Wisconsin in Madison, a trek of almost 1,000 miles, he does so by hitchhiking and hopping freight trains. When he gets to Madison, he’s hungry and has only 37 cents left in his pocket. Fortunately, he finds a job at a diner that pays in meals, and that night he finds a second job at the YMCA that provides a bed. He sets out the next day to find work to cover tuition and books, but his first day on the streets searching for employment doesn’t bring success, as no one can afford to hire help.

Then, as Pickle calls it, the “crushing blow” comes: when he goes to enroll in college he discovers that out-of-state tuition is $100 per semester. He writes: “I had never in my life had that much money at one time! The registrar thought I was crazy. He said, ‘Why don’t you go back to Mississippi where you belong? Don’t you know a man can’t go to school without any money?” Instead of giving up his dream, he deals with the setback by registering to vote. He will establish residency, but it’ll take a year. His feeling at this point, coming all this way for nothing, is despair (he’ll later refer to it as a time when he felt he “barely existed”). But, as he’d write in later years, he held on to one thought: “Dr. Carver had started with nothing, and so could I.”

The biggest hook for me was what I hope others will consider the obvious: this relationship (and others like them) occurred decades before the Civil Rights Era in the Jim Crow South. It’s a scenario that I believe we have been led as a nation to believe was too rare to mention, even though the truth is the opposite: good people do good things often. Throughout our country’s history, there have been individuals who have worked hard to create a better world. These stories are out there, waiting to be told, and we need them to unite us.

I also thought of how important these inter-generational non-family relationships are, and why we don’t make them more of a priority. What could be more satisfying, if you think deeply about it, than helping another person, who has drive and a good heart, succeed?

Carver mentored many young men (the estimate is over 50). These relationships lasted for years and included much correspondence in letters and occasional personal visits. Unfortunately, a significant amount of Carver’s personal correspondence was lost during a fire at the Carver Museum at Tuskegee in 1947 that also destroyed almost all of his personal artwork. It’s uplifting that families have not forgotten.

Carver was made to be a fantastic mentor and went about it with mutual respect, humility, and joy. As Carver put it, “In my work I meet many young people who are seeking truth. God has given me some knowledge. When they will let me, I try to pass it on to my boys.” (GWC to Jim Hardwick at the YMCA Blue Ridge Conference in 1922)

I’ll leave you with one of their beautiful exchanges. I hope it’ll encourage you to buy this book for those in your life (maybe yourself!) who are mentors at heart or for those who need a mentor. Let’s revive this beautiful practice!

In one exchange of letters, during 1932:

Pickle: “The people here in the North cannot understand why I, a full-blooded Southerner, should be so crazy about you. But I have only one answer for that, the educated classes of both white and colored know that the only way that the race question will ever be settled is to raise humanity above the narrow, self-imprisoned barrier of race. Honestly and frankly, I know no man anywhere who I admire more than I do you. . . . When a man’s a man, we don’t think so much who he is, but what he is. He can and should do worlds for people as you have done and are doing.”

Carver: “You are right, many cannot see what you see. I have the same thing to endure from my own people. They cannot understand why I have white people always hanging around me, as they call it. I consider it a compliment. Anyone who cannot get away from self, sufficiently far to see the God in man, regardless of nationality, complexion, or religious belief . . . are quite positively absurd to me. I love them because God speaks to me through them.”

************

You can buy a copy of One of His Boys at Amazon.

Want to gift some inspiration? The BEST biography on George Washington Carver (written by a white woman during the Jim Crow era) can now be purchased online.